Or how I scanned 10 million websites with a friend for security contact information

Preface

Companies worldwide struggle to get a better security posture, yet many are overlooking a new and free possibility to improve their security. And who doesn’t like “free”?

Everything exposed to the internet is expected to hold up against a constant battering. This ranges from regular and expected use, systems overload / DDOS, abuse of misconfigurations, zero days and threat actors trying their best to breach systems using any other technique they can.

But good hackers are also looking for security issues. Some are driven by curiosity, fame, karma or just the feeling to do the “right thing” – of course if you’re participating in a bug bounty program, getting paid usually helps too.

There are three parts to helping someone with a vulnerability. First you have to find it, then you have to describe it, and then you have to report it.

We know there are already lots of people looking for vulnerabilities, but the next two parts … well, it’s a problem. Writing everything down in order to explain it to someone else is just tedious, but it’s part of the job.

Reporting hell

But the third hurdle – reporting – it varies a lot from unproblematic to impossible. Take your own company as an example … let’s say I’ve found a security problem with your website. How do I tell you with minimal fuss?

Do I call customer service? Do I try to find your CIO on LinkedIn? Email to abuse@companyname.com? How should I know – and even if I get through to someone – if it is the right person, if they understand one word of what I’m telling them, or if they even can tell me who is the responsible person to talk to? Talking to someone that doesn’t understand what you’re saying might land you in trouble, ending up with legal action because of misunderstood intent.

The reporting hurdle is bigger than you can imagine. Someone has gone to the trouble to find a problem, are willing to report it, but now have to waste their time trying to figure out how to tell you. Troy Hunt, an active security researcher who collects breaches and is behind haveibeenpwned.com has struggled with this for years, sometimes ending up asking publicly on Twitter “does anyone know how to reach Company X”, and everyone but Company X knows they’re about to get the news about a major breach of their systems.

A (wild) solution appeared

Because of this, Edwin Foudil introduced the “security.txt” solution in September 2017. The general idea is that you can publish a simple machine and human readable text file on your website, which informs security researchers on how to reach out to your company, in case they need to responsibly report a vulnerability or other security problem.

This was 4½ years ago, and it was accepted as an official standard RFC 9116 in April 2022. Except for more possible data fields nothing truly earth shattering has changed in the four years since it was ‘invented’. Now it’s simply an ‘official’ way of doing this.

Lots of security researchers knows about the security.txt file, because it’s quite obviously the easiest way to find out where to do with the problems you wish to report. But what are the odds of finding the answer using this? Let’s find out!

Why and what

During one of my hour long phone conversations with my good friend Daniel Card / mRr3b00t (yo!), he told me about an experiment he did with downloading the index page of some web pages, in order to scan them for JavaScript malware (basically just feeding them to Windows Defender as files). Since we’re probably nuts, we agreed that something like this was a great idea, and we should aim higher. So we discussed scaling this to 1 million sites – and since no one stepped in as an adult and said “let’s not do this” that was a plan.

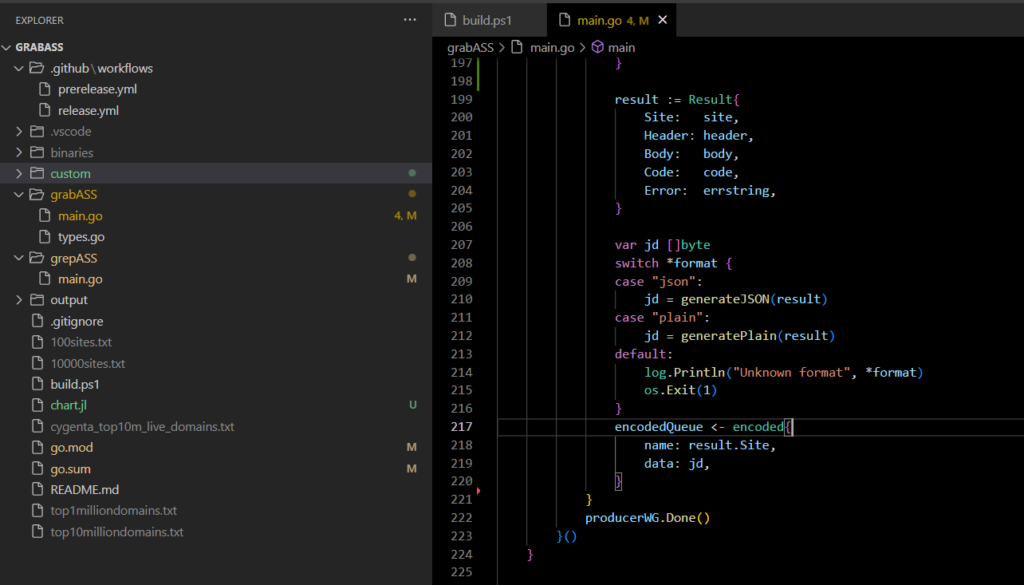

While there are other options, I quickly settled on writing my own high performance multi-site mass downloader – because I could, and because the others I found weren’t really 100% suitable or the performance sucked. This became grabASS (grab Accelerated Server Stuff) which is now freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/lkarlslund/grabASS).

And with fast software, fast internet and fast computers … downloading things from 1 million websites could be done in less than a few hours! So why stop there? You could just as well aim even higher!?

Then I located a list of the top 10 million domain names, and started experimenting with that. We posted about this on Twitter, and either by coincidence (or by lending inspiration?) someone else compiled a list of 10 million ‘functioning’ domain names on GitHub. So basically what they did was grab all domain name lists available, combine them, filter out the dead domains, and publish this compilation. This list is available from https://github.com/cygenta/top10million as a huge text file with one domain per line.

Great, now we didn’t have to do that part, and we’d have more ‘live’ domains to work with! So for doing the downloading part this was the source of domains. Rather than AV scanning the sites, the project forked off in another direction, because we thought looking at security.txt would also be interesting … we’ll get back to the AV scanning in the future.

Off we go, and since we’re just requesting a small static text file, this was completed in less than 12 hours – with the CPU in the pfSense firewall being the actual bottleneck capping out at around 650Mbit and 300 connections/sec in peak periods.

The methodology is as follows:

- If the primary host isn’t found (domainname.com), we retry with www in front (www.domainname.com)

- If the domain is dead / unresolvable, we stop processing

- Then we try to grab (www.)domainname.com/.well-known/security.txt and look at the results

- Non-responsiveness gets another retry

- Code 301/302 redirects are followed

- Code 200 results are stored

- The rest is discarded

You can replicate this part of the experiment with grabASS if you want:

./grabASS --sitelist=cygenta_top10m_live_domains.txt --showerrors=false --outputfolder=11m-results-security-txt --urlpath=/.well-known/security.txt --perfile=1 --storecodes=200 --format=plain --compress=falseNote: I’ve re-run the collection with different parameters since publishing this blog post, with minor impact to the results. See the update at the very end of this post.

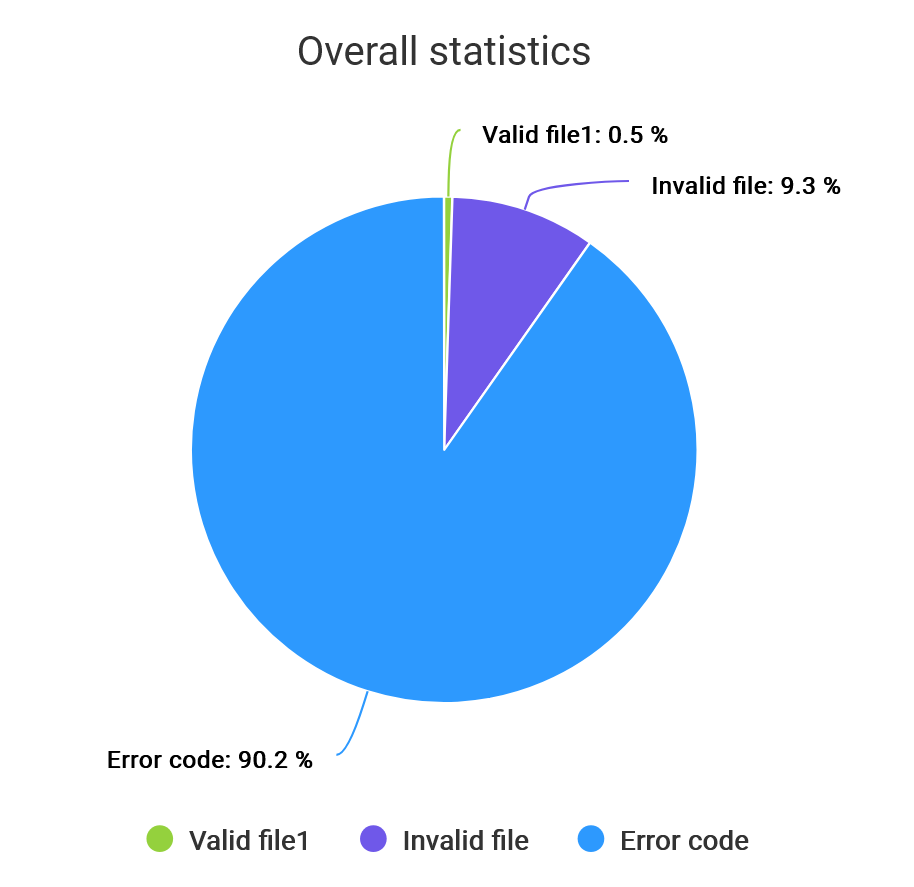

That gave approximately a 10% success rate, with 10063833 domains yielding 983520 responses.

Wow! 10% of the 10 million sites have implemented ‘security.txt’? Can you actually believe it – that would be a massive success.

Me, coming up with a quote real quick

Well, unfortunately that wasn’t the case. You see, rather than responding with a 404 “page not found” error, lots of sites either redirect you to (or just present directly) a nice looking page with a 200 “ok” status code. So the human interpretation is “not found” while the machine interpretation is “this is great”. Thanks, webmasters!

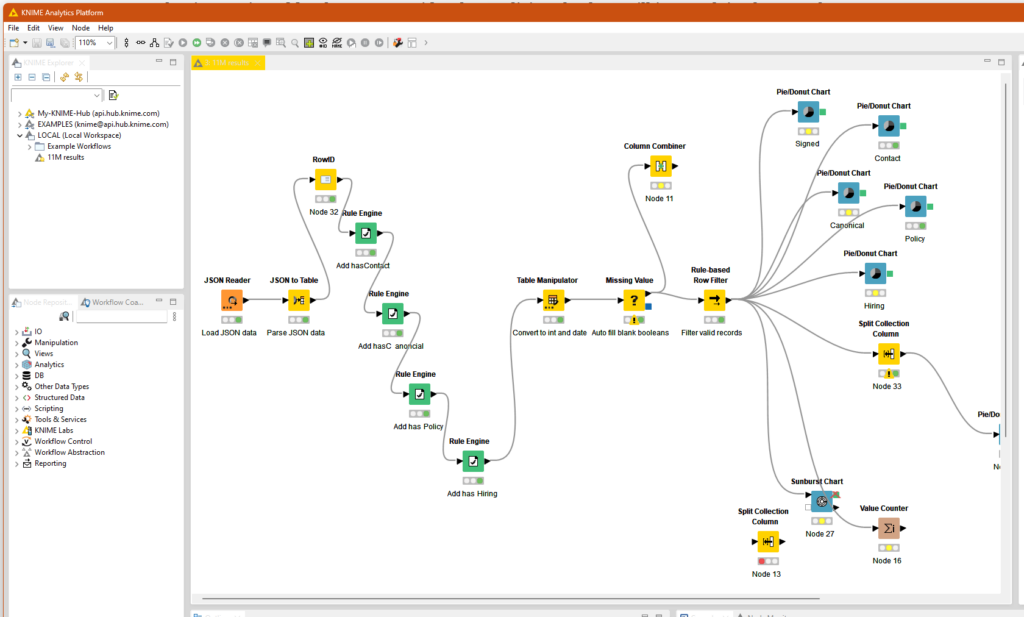

In order to make filter out these false positive results, we can look for results that has at least one of the following fields defined: Contact, Canonical, Policy or Hiring. The Contact field is the bare minimum, so we could just look for that … but alas, some have implemented security.txt but missed the bus on what the point was: They might point to their policy, but not to their contact method. Thanks, security webmaster/security/standards n00bs! Now you manually have to hunt though the human readable security policy in order to figure out how to contact you.

(first time using this, so this might not be the best way)

Anyway, this filtering brings the number down to 52248 results, which is now 0.5% of the tested sites. A minuscule number, if you compare that to the fact that approximately 25% of all companies experienced some sort of cyber security incident in 2022.

May the odds be ever in your favor. Only they’re not. Actually the odds of getting hacked (25%) is 50 times bigger than a white hat hacker can report a vulnerability to you via security.txt (0.5%) … terrible!

That is not nice when you consider that malicious hackers will just exploit whatever they can, ransomware you, sell your data or use your systems as a C2 server, send spam, mine cryptocurrency or whatever they damn please.

A few companies are leading the way

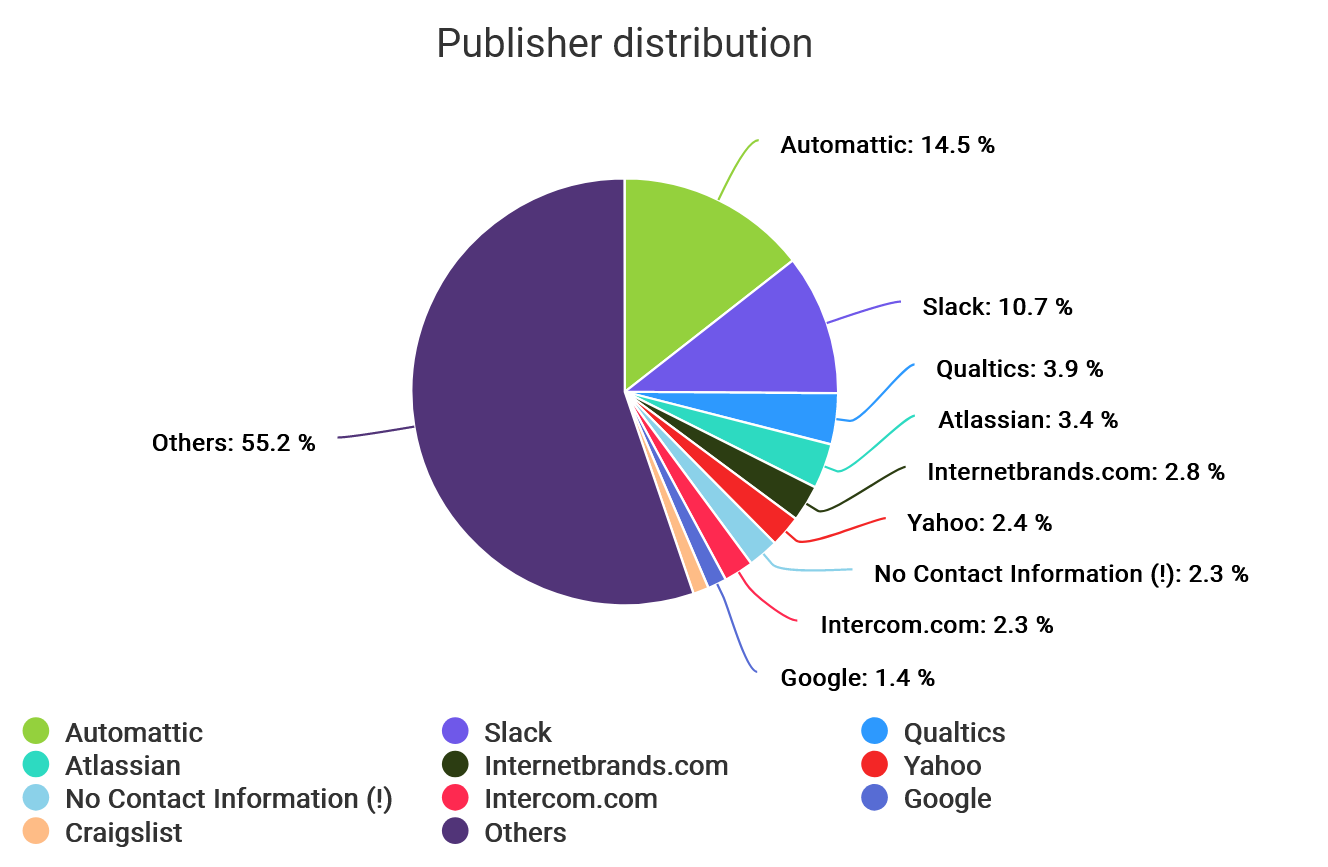

From the 52K results there is a pattern: quite a lot of the responses ‘Contact’ field point back to a small amount of companies. Directly translated this means that large companies that runs many websites (due to localization, different branding etc) represent a huge chunk of the results.

So almost 15% of the scan results points to Automattic’s HackerOne page. This is great, because it means that they’re scaling with it, but it does offset the results a lot. More than 10% of the results are Slack servers, and they point at Slacks HackerOne page. This pattern continues, and you end up with just 9 companies being responsible for 43% of the results in this scan (and 2.3% having made a security.txt only to NOT include the required Contact field!?).

It’s great that the larger companies have adopted using the security.txt file format, but it also means that your odds of hitting a system that has implemented this is even smaller, unless it’s one owned by a large company. Now we’re down to less than 0.3% hit rate if you look at the total 10 million sites scanned.

Another data breakdown

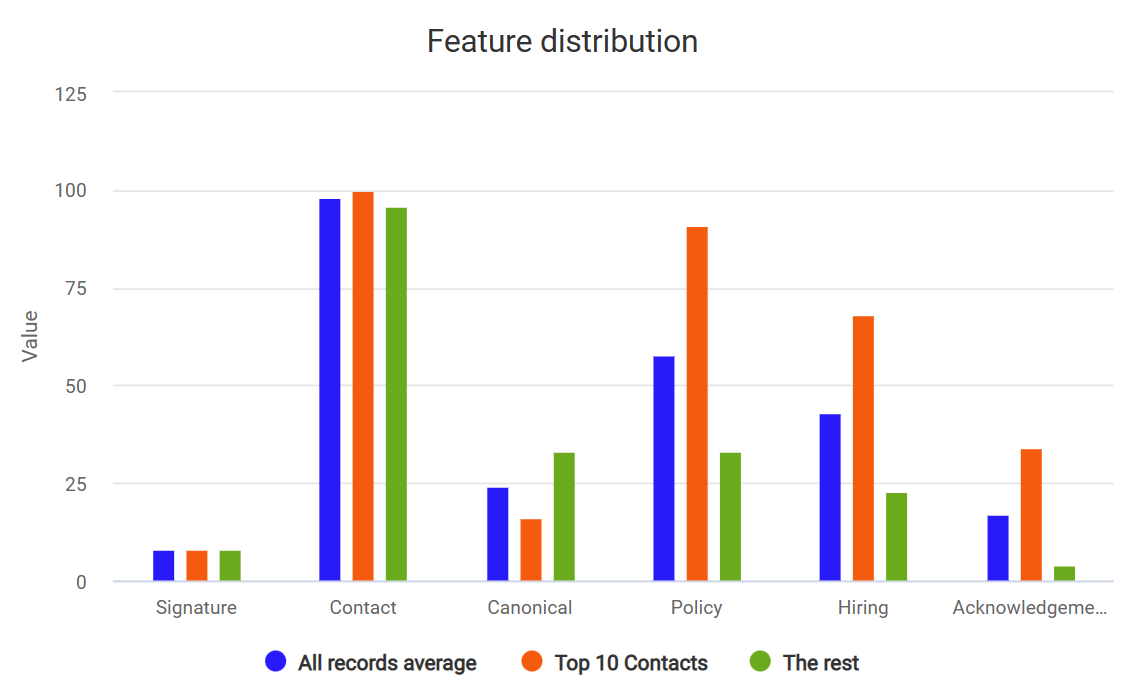

So since there’s a difference between the top 9 companies and the “rest”, why not look at how that distributes on other possible fields in the same file?

Unsurprisingly it looks like the large companies are better at using the optional features such as a reference to ‘acknowledgements’ which 34% include compared to just 4% of the rest of the sites (usually a page where you get credit for having helped them). Getting hired is also easier at a large company with 68% including it, compared to just 23% of the rest of the sites (which isn’t too bad honestly).

The surprise is that the ‘canonical’ reference is less popular with large sites, but I’m guessing they’re using the same file for all sites, and it would be troublesome for them to generate unique files per site (just a hunch)

Help everyone – and yourself – implement security.txt

You can also get the warm fuzzy feeling of implementing this! There’s probably no comparable way of improving your odds of getting others to help you with pointing out security issues on your website.

To do this, you’ll need a valid security.txt file – simply visit https://securitytxt.org, fill in the form, download the file and get your company website admin to publish it under the correct path.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, but I think implementing this is your biggest bang for the buck at the moment. Just do it! It took me 5 minutes to implement on this blog. Maybe it’s worth your time too?

Update

A nice person on Mastodon informed me that my statistics might me imprecise, as it’s also valid to place the security.txt file in the root of the website, not only under the .well-known subfolder. So 6 hours and 33 minutes later, I can see that this brings the coverage to 63K sites, up from the 52K previously discovered. It also changes the top 10 distribution by replacing the 9th and 10th place with Moodle and Reddit (was previously Google and Craigslist). I have opted not to re-write everything above, as this has only minor impact on the other results.